Our approach has aimed to be as participatory as possible, acknowledging and learning about the many challenges and opportunities that this approach involves. We are inspired by the power of stories as a window on the world, and a mirror to see ourselves.

We are not naïve – we know that power dynamics are structural and that one modest project cannot overcome all of the challenges, but we hope to have shed further light on some of these.

Based on the premise of giving space to multiple ways and perspectives of accumulating knowledge, we have sought to decolonialise our ways of working and to listen, co-create and adapt our project design along the way.

Our approach has been through many ebbs and flows due to a range of circumstances, not least the challenges posed by the pandemic, but has maintained a commitment to the notion of place-based knowledge as multidimensional (Zaragocin, 2021): that’s to say, acknowledging the range of influences and pressures on the lives of the young women with whom we’re working – as community activists, as students, as young mothers, as daughters.

Amidst intense Covid challenges, we adapted to online working from the start (June to August 2021) with trust-building exercises using audio-visual activities. Two subsequent fieldwork visits allowed us to work to create short films that highlight their environmental concerns at the same time as supporting the development of leadership skills, and to share those with their communities.

We came across many different challenges: connectivity, access to technology, how technology is not free of structural power relations. We had to acknowledge these relations and also to try to find creative ways to overcome them. For example, some of the young women had no access to cell phones or connectivity and therefore couldn't take part in the workshops, but we still see several of them on screen being filmed by those who could access the technology.

Following cultural theorist Donna Haraway (on ‘situated knowledges’), we might say that our research, from a feminist and feminine perspective, is relational, intergenerational, partial, and always contextual. Moreover, despite the potential imperatives of the broader organisational structures within which we all operate (whether university or community organisation) we have aimed to take as the starting point for each film the specific motivations and interests of each individual young woman, rather than creating big picture panoramas from an organisational perspective.

And in all this we have rediscovered film as the centre-point of our collaborative tool of engagement, picking up lessons from important Peruvian media groups such as the Escuela de Cine Amazonica, Chirapaq and Grupo Chaski. We have proudly mobilised the expertise and experience of EmpoderArte, and feel that our project serves as further evidence of the capacity of ‘film [as] a method of conducting research…, producing new knowledge and … disseminating this knowledge to diverse audiences’ from a feminist standpoint (Sophie Harman, 2003), ie through young, indigenous, rurally-located female eyes.

Film production was the method used during our first fieldwork visit in December 2021, when members of the research project team visited the region of Junín to conduct workshops in filmmaking that enabled the hermana participants to articulate their ideas about urgent issues in ways that could be used to highlight these challenges to diverse audiences (in their communities and beyond).

As such, our OMIAASEC community partners represented themselves and their communities through their films, which were then edited through a series of online editing workshops led by Karoline Pelikan from February 2022 and the time of our second fieldwork visit. During these online workshops, ideas, advice and opinions were also sought from the hermanas on aspects such as logo, design, animation, credits, voiceover and translation.

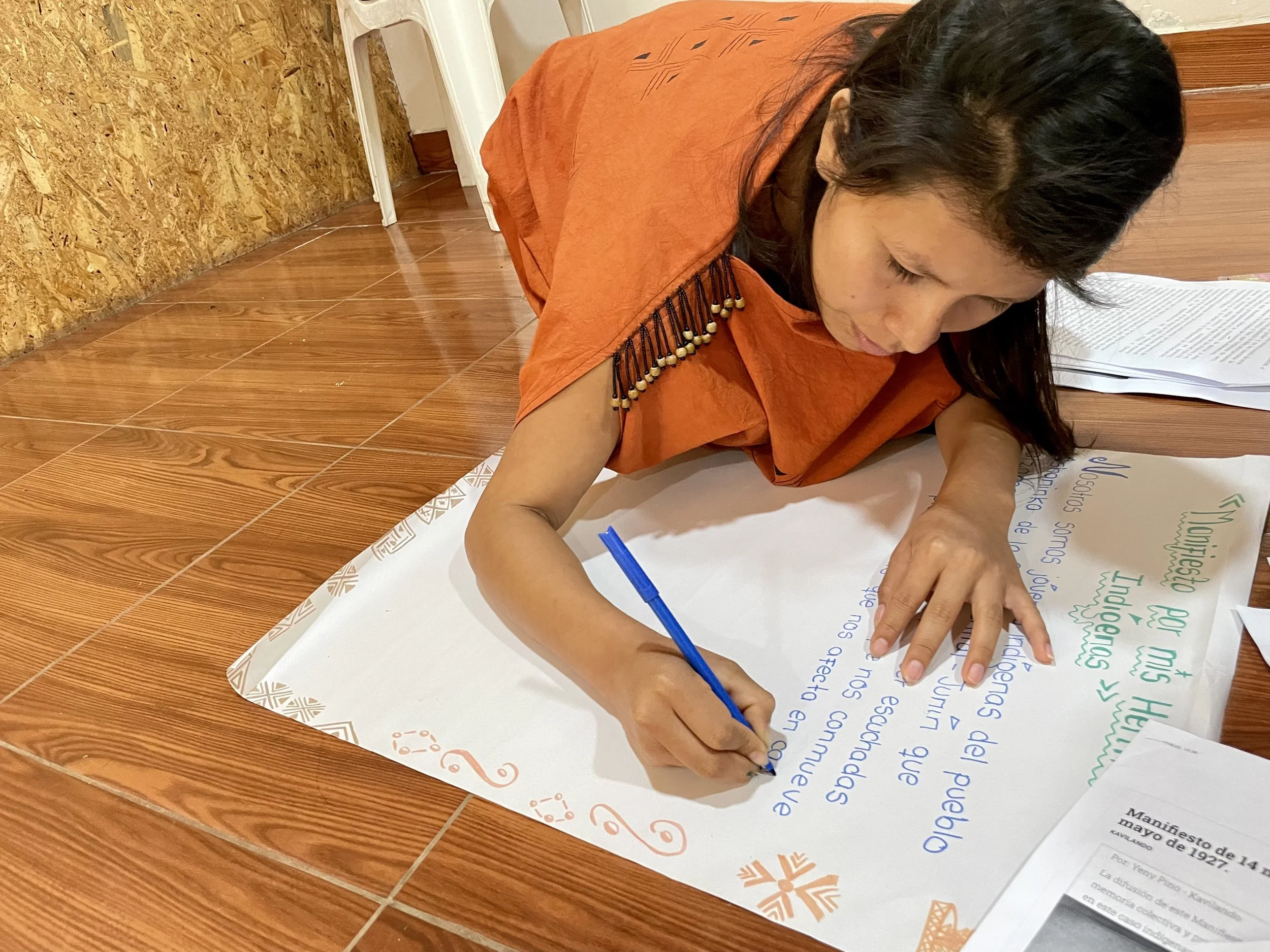

The first stage of dissemination took place during the second fieldwork visit in August 2022. A workshop weekend was held first, during which the team watched and discussed the edited films with the hermana participants, mainly in terms of their content. We also worked led by Roxana Vergara on a ‘manifesto’ that sets out the most urgent concerns of the young hermanas, in their voice.’

We held workshops on how best to present these films in their communities, before embarking on 4 days of visits to their communities located along the river Perené where we set up impromptu screening facilities and shared the films with intergenerational audiences, resulting in lively discussion, debate about the effects of climate change, the importance of ancestral knowledge and language learning (including through song), and even sharing of recipes and other cultural customs.

Since that second visit, we have been developing the project website (drawing on ideas and designs discussed with the hermanas) that now serves as a hub for project outputs and links to the social media that keeps us in touch and up to date with relevant projects, events, groups and issues.

We are also now engaged in disseminating our findings through events, presentations, teaching sessions, workshops, festivals and publications, several of which are highlighted on this website.